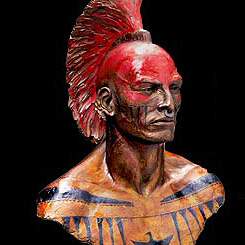

Bronze edition: 20 | Height: 30″ (with base)

“According to Canadian tradition, he was not above middle height, though his muscular figure was cast in a mold of remarkable symmetry and vigor…his features had a bold and stern expression; while his habitual bearing was imperious and peremptory, like that of a man accustomed to sweep away all opposition by force of his imperious will… though descriptions of his appearance vary, all who mention him testify that he had an air of a commander of men; he was proud, vindictive, war-like and easily offended.”

Francis Parkman, The Conspiracy of Pontiac (1870)

“He puts forth an air of majesty and princely grandeur and he is greatly honored and revered by his subjects”.

Maj. Robert Rogers (1765)

“He puts forth an air of majesty and princely grandeur and he is greatly honored and revered by his subjects”.

With the fall of New France at the close of the French and Indian wars, the pivotal role played by the Indians in that titanic struggle ended. Once, they held the balance of power and were courted by both imperial powers. Now they were scorned by the English and General Amherst considered them a troublesome nuisance. This prevailing attitude would have tragic consequences for English soldiers and settlers alike.

The vast majority of the Great Lakes tribes had been bitter enemies of the English. These children of the French King now chaffed under the arrogant rule of the victorious English and watched sullenly as, one by one, they took possession of the French forts in the Ohio country.

Pontiac, who had led his Ottawa warriors in the annihilation of General Braddock’s army near Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) in 1755, appeared at this critical juncture. By the force of his intellect and charismatic personality, he was able to galvanize the growing hostility and resentment that seethed below the surface. By circulating war belts and picking up the hatchet in attacking Detroit in the Spring of 1763, he helped to unite 18 different tribes stretching from Lake Ontario to the Mississippi. He was the catalyst and inspiration for the largest and most successful Indian resistance ever witnessed in North America.

In a series of stunning military victories in the Spring and early Summer of 1763, the Engish presence in the old Northwest was virtually eliminated. Eleven English forts and outposts stretching over present-day Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan had fallen. The only holdouts: Niagara, Fort Pitt, and Detroit lay under siege. Ottawa, Chippewa (Ojibway), Miami, Sauk, Huron, Pottawattamie, Delaware, Illinois, Shawnee and Seneca among others, had united to drive out the English and prepare the way for the return of the French King. More than 2000 English soldiers were to die with notable losses inflicted at the fort at Michilimackinac (Michigan) – through the clever ruse of a lacrosse game to lull the garrison, involving Sauk, Ottawa and Ojibway, the entire garrison was cut down; (see “War’s Younger Brother”) and near Niagara Falls at a place, thereafter named Devils’ Hole, two companies of British regulars as well as 30 soldiers accompanying a convoy of 25 horses and ox-drawn wagons, many of whom plunged to their deaths in the chasm below, were almost completely destroyed in an ambush by 500 Seneca and Ottawa warriors. In addition thousands of settlers all along the frontier were casualties of the war, killed, captured or made homeless refugees fleeing east in panic.

Ultimately however, the Indians inability to capture Niagara, Fort Pitt and especially Detroit (for to do so would have entailed a conscious decision to sacrifice many warriors, something they were unwilling to do) and the failure of the French King to come to their aid caused the resistance to finally collapse.

Realizing the inevitable futility of defeating the English but never defeated militarily, Pontiac, unbowed, formally signed a treaty of peace with Sir William Johnson at Oswego in 1766. He lived the last five years of his life at the Ottawa village on the Maumee (Ohio) but was assassinated on a visit to Illinois by a Peoria Indian in 1769. The idea of a pan-Indian resistance which he inspired did not die with him however. It was revived again in the diplomacy of Joseph Brant, a Mohawk chief, at the close of the Revolution; in the military defeat of two American armies by the Miami chief, Little Turtle in the early 1790’s, and finally by the Shawnee Tecumseh in 1811 having been inspired by the ideas and the memory of Pontiac.